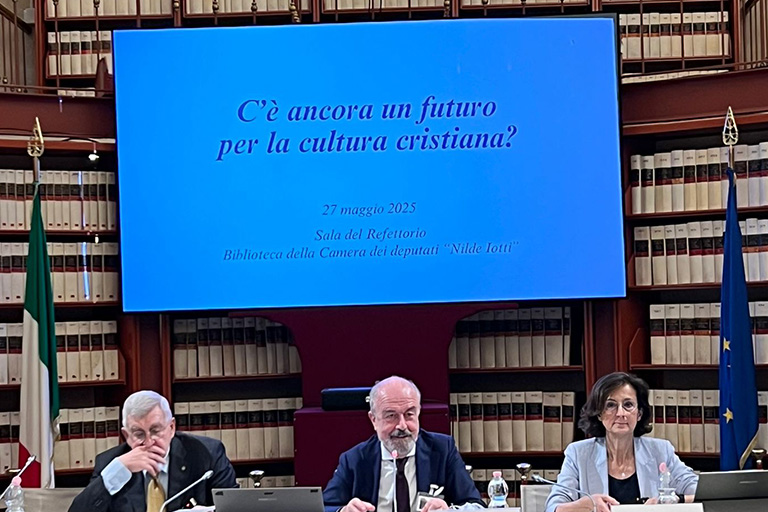

Refectory hall of the Chamber of Deputies, Rome, May 27 2025

On the occasion of the release of the volume Una cultura che trasforma il mondo. La vita come relazione (published by Ares), sociologist Pierpaolo Donati (creator of the general theory for the analysis of society called “relational sociology,” professor emeritus at the University of Bologna, member of the scientific committee of ROR) met with Professor Marta Cartabia (President emeritus of the Constitutional Court and professor of Constitutional Law, Bocconi University of Milan) at the Refectory hall of the Chamber of Deputies on May 27, 2025.

Donati’s volume collects insights from a debate published in the Agorà section of the Catholic daily newspaper Avvenire on the theme “Catholics and culture.” With this premise, to the question: “does a Christian culture exist?” Donati provocatively responds: “Perhaps yes, perhaps no.” The central point is that Christian culture is not a doctrine, it is not an ideology, it is a modus vivendi: daily life lived as relationship, which connects the human with the divine.

Faith requires a culture that embodies it; faith is nourished by human relationships. Donati starts from the premise that the indicator of historical turning points in a society is the theological matrix. The latter, although not visible, configures the foundation of a society.

For Donati there is a possibility of a future for Christian culture if we reason starting from this new scenario: the dream of a worldview that is in light of relationship. Each of us should think of ourselves in relationship. Christian culture, if lived in this light, possesses in potential the capacity to transform the world starting from the relational networks that intersect in daily life. The problem – the scholar emphasizes – is that we don’t know what relationship is. Regarding the sociology of relationships, Donati recalls: the social fabric is not represented by freedoms that clash but by relationships that are established. Individual consciousness itself springs from being in relationship: we can know ourselves and know only through relationship: it is the relationship that speaks, that tells us who we are.

Relationships also constitute the solid foundation for resolving conflicts. Donati emphasizes that by seeking to establish which relationships we want, we will succeed in illuminating the world with the very soul of relationships, not leaving space for the pervasive experience of aggressiveness, constantly at the center of news reports.

Marta Cartabia, for her part, has emphasized the importance of a redefinition of Christian culture. All contribute to such a process with the ordinariness of daily life, which, contrary to what is believed, has no less value than public life. Ordinary living affects and forms a culture deeply. This idea of culture as ordinary practice is very relevant because, as the former minister emphasized, citing a passage from Donati’s book, that references the letter to Diognetus: “Christians are in the cities of the world” and often “the image of Christian culture that we have does not coincide with that of the letter”.

Relationship, the constitutionalist further reflects, indicates both a method and content. From this perspective, relationships can truly constitute the fulcrum for the development of a healthy society. We have had the self, the subject, at the center, so why not now place relationship at the center (it’s not about putting the self in storage but having the self in relationship). The theme of identities in groups has been at the center of legal debate but no one has studied relationships in legal terms. This is curious, Cartabia observed, if one thinks that they constitute the matrix of our Constitution, whose first four titles are: civil relations; ethical-social relations; economic relations and political relations. And indeed, looking closely, the paradigm of our Constitution is relational!

Relationship is therefore content, apparently elusive, nonetheless its positive or negative effects can be concretely observed. Relationships can become unhealthy: we are in an era of hyper-conflictuality, which was brewing in a culture that did not know how to look at and care for relationships.

But relationship also has a second valence, Cartabia emphasized starting from Donati’s text: it is a method. This is a precious aspect. Relational culture is similar to shared research: it allows approaching problems starting from the relationships involved, through which it is possible to conduct research into the causes of wounds to then return to a synthesis equilibrium. Citing her direct experience as an exponent of restorative justice, Marta Cartabia recalled the book Il libro dell’incontro (published by Il Saggiatore) which narrates the confrontation between victims and those responsible for the armed struggle of the Red Brigades, unfolded over eight years of meetings. Having established this reparative relationship, Cartabia explained, opened a new chapter in criminal justice, because in the face of certain wounds, not even the most just sentence is enough.

Daily life, Donati observed in conclusion, has been devalued since Aristotle onward: the master can afford to exit from ordinariness, which has had a negative place throughout history. Even from an interreligious point of view, faith is what emerges from intersubjectivity with God. It is a common world that connects public and private because daily life is what puts us in relationship with everything: with the home, with work. It is the world of intersubjectivity, that phenomenology has studied at length, but to which it has not recognized an ontological substance. Conduct of life, according to Max Weber, changes the world: it is what characterizes daily existence. One must not forget that the latter for a Christian is the object of sanctification. It does not mean performing spectacular gestures: sanctification is making every act of daily life just. Normally daily life is where we find the connection with God in ordinary things; the connection with God gives every daily event its profound meaning. The dominant culture instead leads us to think that daily life is a life of repetitiveness and boredom. Teaching even the new generations that daily life is an opportunity for joy in the small things of every day: this is profoundly Christian.